Kevin Murphy (00:01)

Welcome back to What Matters Most, Sands Capital’s podcast series in which we explore some of the trends in businesses that are propelling the pace of global innovation and changing the way we live and work today and into the future. Today, I’m joined by my friend and colleague Sr. Research Analyst Massimo Marolo to discuss a consumer business that really seems to have a hold on its niche market.

In India, jewelry is a very big deal, and the demand for gold nears that of the U.S., Europe, the Middle East, and most of Asia combined. So today, we’re taking a detailed look at Titan, India’s jewelry giant, and walking through the investment case with Massimo. Massimo, thanks very much for joining us today.

Massimo Marolo

Thanks, Kevin. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Kevin Murphy (00:41)

You know, we’ve owned Titan for a long time. I think it goes back to one of our first investments in the emerging market space.

And we’ve owned it off and on. And I know that you were responsible for underwriting or re-underwriting the investment case most recently. So you have a depth of knowledge on this particular business and this particular industry in general that I think will be fascinating to dig into today.

Massimo Marolo (01:06)

As you mentioned, I’ve been following Titan for many years and India more broadly for about a decade. I’m excited to talk about it today.

Kevin Murphy (01:14)

Great, so all right, let’s get started. Titan, as I mentioned, is India’s largest jewelry and watch retailer. But before we dive into the specifics of the company, let’s step back and talk about the Indian jewelry industry broadly. Why is this, in particular, a promising business space?

Massimo Marolo (01:30)

Sure. So yes, gold is a huge deal in India. Imagine that the World Gold Council estimates that India’s yearly consumption of gold is approximately 700 to 800 tons. That’s about 25 percent of global demand, more than the U.S., Europe, the Middle East, and all of Asia (excluding China) combined.

All of it or nearly all of it is imported. So that’s a real demand pull. At today’s prices, which I think are about $2,300 an ounce, that’s approximately $55 billion worth of gold or 1.6 percent of India’s GDP [gross domestic product]. But what’s even more incredible is that the overall stock of gold. So not what’s purchased every year, but the cumulative amount of gold that exists in India sits at over $1 trillion dollars. And that’s close to 30 percent of India’s GDP. So enormous. There’s really nothing quite like it across any other consumer category worldwide.

Kevin Murphy (02:34)

OK, excellent. You mentioned the cumulative amount of gold in India sits at over $1 trillion. Talk about the source of gold for the jewelry manufacturing industry. Where is that coming from? Is it raw material from mines? Is it this recycled gold that’s sitting in people’s houses? How does that work?

Massimo Marolo (02:52)

Sure. So Titan says that approximately 40 percent of the gold itself is recycled, as you point out. Now, what does “recycled” mean? Basically, it means a customer has a piece of gold at home; maybe it’s even a jewelry piece that they’ve held there for a very long time.

It’s of a style that doesn’t quite resonate with that consumer anymore. So they want to utilize that gold and turn it into something different that is perhaps more modern or more akin to their sense of style at that point in their lives. So they will show up at a Titan store, as to other jewelers across India, and ask for that piece to be recycled. So you bring in your piece. This instrument will measure the content of gold. It’ll then be melted. And then, you can essentially have it shaped as whatever new piece you want. Be it a pendant, be it a ring or bangles. It really depends.

So Titan will essentially buy that piece or recognize that piece at the price of gold at that moment in time. And then they will apply a “making” charge, which varies by jeweler, and this is really where Titan makes most of its money. It can apply making charges anywhere from high single digits to high teens in some cases if the piece is quite complex and sophisticated.

This is, by the way, higher than the making charges that other jewelers will charge. But that’s because people trust Titan, and also because Titan, being a completely vertically integrated operation, has more styles and breadth of styles that it can offer consumers. So then, the piece will then be sold again to the customer with the making charge. And that’s about 40 percent of the jewelry sales that go through Titan. The rest, as you mentioned, is essentially imported. So it’s bought from some of the entities that will import and refine gold into India because the vast majority of Indian gold is imported. These will be imported from a variety of sources around the world.

Kevin Murphy (05:10)

Yes, can you give us an idea of what sort of market share we are talking about? Who are some of the big players, and where does Titan fit into that?

Massimo Marolo (05:18)

So at present, Titan has approximately an 8 percent market share in jewelry, which we think can evolve to 12 percent to 15 percent long term. Now, in terms of market, it’s a highly fragmented landscape. Estimates vary, but organized, more formal competitors represent only about 35 percent of the market, with the rest being unorganized mom-and-pop type of operations. You should see some of these stores. They’re, in some cases, as small as 200 square feet.

Some of the other players are companies like Malabar, Kalyan, PC Jeweller. Those are really the more important peers, although none of them quite come close to Titan’s market share. But they are important. Some of them even have a national presence.

But really what matters is the gradual share take that will continue to take place from these unorganized jewelers. The way the market is changing—the way it is evolving—is making it very difficult for some of these smaller operations to compete. You have to keep in mind that the category is quite asset-intensive, meaning gold is not cheap. And so even the smallest amount of inventory can represent a very big absolute number. It’s also not something that people are purchasing on a daily basis. As you can imagine, the ticket price can be quite high. So it’s not unusual for a jeweler to have a piece sitting there for a year before it gets sold. So the working capital dynamics really favor those more formal competitors who can absorb that, plus have those bigger store environments where customers can come and browse.

Whereas, if you’re a small mom-and-pop operation with a 200-square-foot footprint, you really don’t have a lot of selection to offer and that ultimately puts you at a disadvantage. And then, if you couple that with some of the reforms that have happened in India over the last decade. The demonetization, for example, was a very big deal where suddenly, from one day to the other, India basically made the 500 rupees and the 1000 rupees banknotes illegal, which essentially purged a lot of gray- and black-market money. And if you’re one of these smaller mom-and-pop operations, you know, it’s hard to say, there’s no real official estimates. But gold, as you can imagine, was a very convenient place to recycle gray or black money, and so something like the demonetization that happened clearly pushed the market in favor of some of these more formal, legitimate operations.

Kevin Murphy (08:04)

Yes, before we go specifically to the company, one question I had popped into my head here.

Now, correct me if I’m wrong, but I think part of this, the case here is a move to more daily wear. I’d like to see that become a greater share of gold sold for Titan. But kind of above that, both wedding and daily wear, we’re talking about a younger population. What’s your best guess on the stability of that demand? Is it likely, or do you consider a risk that population would maybe start spending their disposable or discretionary income on things other than jewelry? Maybe looking at electronics or more modern consumer goods?

Massimo Marolo (08:45)

Sure, sure. So, we’ve done a lot of work on the ground, and it continues to suggest that the affinity for gold remains deeply entrenched. Of course, there’s recurring fear around consumers growing less keen on gold versus smartphones and other such experiences. With a median age of 28, India is, by default, a young country. But multiple data sources show spending on jewelry and watches actually accelerating since 2010, growing at approximately a 9 percent CAGR [compound annual growth rate], whereas in the previous decades from 2000 to 2010, that demand was growing at approximately 3 percent. So, there’s really been an acceleration. And we’ve done surveys asking such young people to comment on where they will be allocating spend going forward. And it all suggests that they continue to see jewelry as an important area for discretionary spend going forward.

Kevin Murphy (09:48)

All right, great. Well, we started to talk about the company specifically, so maybe let’s talk about when it was founded, its particular brands. And I’d also be interested to hear about …

We talked about the formal competition, but the informal competition is interesting too. And trust. I would imagine there are kind of two sides to that coin. You trust the brand Titan. But at the same time, you probably also trust your very local jeweler as well. So maybe take us down that path and the specifics of the company.

Massimo Marolo (10:18)

So Titan was founded in the 1980s. It was a joint venture between the Tata Group and Tamil Nadu’s Industrial Corporation. They have about 1,000 jewelry stores, and 70 percent of them are franchised. The flagship jewelry brand is called Tanishq, and it targets the upper-middle-class urban female customer with a disposable income of $6,000 to $15,000-plus. That brand accounts for 80 percent of sales. They also have an ultra-premium brand called Zoya with only about 10 stores across India. They have an affordable entry-point brand called Mia, with about 200 stores, and then an online-first brand called CaratLane, which they actually purchased, that has approximately 200 outlets.

Titan is also present in other categories—watches and eyewear, both promising spaces but representing less than 10 percent of their total sales. So jewelry is really what matters when it comes to the company. In terms of the trust that Titan carries in the marketplace. Titan’s mind share of trust and purity really shines because the industry’s fraught with a phenomenon called “undercarating.” This is basically jewelers scamming their customers by selling pieces that do not contain the level of gold that is advertised.

Tanishq was really the first to introduce the Karatmeter in its stores, which allowed customers to verify pieces’ gold makeup in real time. That was quite revolutionary at the time. And to this day, you will find a Karatmeter in pretty much every other formal jewelry company in India. But when you go to the more unorganized mom-and-pop type of stores, there’s really no such thing because, again, it represents an investment. But increasingly, you’re seeing customers transitioning from these mom-and-pop, unorganized footprints to the Titan-like stores.

Now, the other elements of Titan trust or the trust that Titan carries in the marketplace is that, when it comes to diamonds, for example, it will offer 100 percent buyback at current prices, which is very key to building loyalty in the studded [jewelry] category. And these elements of trust really take time, especially in these smaller communities where the local jewelers, in some cases, often act as bankers. They will finance the purchase. The relationship that a customer will have with the jeweler can really go way back. Oftentimes, people shop at a particular jeweler because their parents used to shop there, and there was a relationship.

But increasingly, as these phenomena of undercarating become more prominent, or at least more discoverable, you’re seeing a gradual shift away from these unorganized competitors towards more formal ones. It will never be an overnight win, but scale and balance-sheet strength can fuel winning value propositions for a very long time.

Kevin Murphy (13:42)

So is it, are they just moving into those markets and taking over the business or are they acquiring some of these smaller jewelers?

Massimo Marolo (13:50)

No, they don’t do any acquisitions of other jewelry stores. They acquired a chain called CaratLane, as I mentioned, because CaratLane was an online-first brand, and they felt they needed to develop an ecommerce functionality.

Ecommerce in jewelry, by the way, remains and will probably remain a pretty small part of the overall business. That is true across many other jewelers across the world. This is mainly because it’s such a high-ticket item, people really want to go to the store to touch and feel the product before they buy it, and the other component is that it’s often a social purchase, especially in India where a wedding is such an important occasion. You will typically bring your family along to the jewelry store and maybe go there more than once to try different pieces. So it doesn’t really lend itself to ecommerce very well. There are instances of that, but it’s probably not a category that will grow to more than 10 percent or 15 percent penetration.

Now, in terms of the stores that Titan runs, 70 percent of them are franchised, which lowers the capital intensity for the company and helps reach some of the lower-tier markets. So we made it a point on regular visits to India of dropping in on some of these franchisees and asking them about the relationship with Titan.

These are, again, for Titan, relationships of trust. So this is not a jewelry chain that is expanding its footprint by multiple thousands of stores, multiple hundreds of stores per year, because it all depends on the kinds of relationships they have with their existing franchisee base. So these are either existing franchisees with whom they’ve already had a relationship for many decades that are interested in entering new markets, or they are new franchisees that come through referral from some other franchisees or some friends of the firm. But these are really cultivated and nurtured in a very careful way because, clearly, they don’t want to get into business with franchisees that might not be able to honor the very intensive capital requirements of running a Titan store.

To give you a sense, It’s not unusual for a Titan store to carry more than 250 kilos [over 500 pounds ] of inventory in a store. At today’s price of gold, that is a very significant amount. Again, to my earlier point, this is not a category where items are being sold every day. So it does require having a franchisee that has a stable financial situation that can really sustain a lower turnover and a gradual win for competitors in their region. So these are all things that take a very long time to develop.

Titan will enter a new market, open up a new store with an existing franchisee, or maybe a new franchisee, and really build from there. It can take three, four, or five years before that store reaches the maturity level of sales that it experiences in some of its more mature markets.

Kevin Murphy (17:09)

Let’s stay on that point about industry fragmentation and the gradual consolidation, talking about franchise and their go-to-market strategy here. You mentioned an 8 percent market share in jewelry, and I think your estimate is that it can grow to 12 percent to 15 percent. How does that compare to other markets outside of India? Is it a much more concentrated marketplace in terms of jewelry, or is it about the same? I guess the question I’m getting at is: Is there a kind of a natural cap to the amount of concentration and share they can take?

Massimo Marolo (17:43)

Yes, that’s a very good question, and we’ve looked at many other jewelry markets around the world. We’ve actually looked at pretty much all of them in terms of data. And jewelry, on average, is a fairly fragmented category.

It is unusual to see a local leader go much above 15 percent market share. And that’s because jewelry, at the end of the day, is a very personal type of purchase and often comes from having a lot of trust in the retailer that serves the local community.

There’s also an element of localization of designs. This is more true in some markets than others, but even in certain European markets, for example, you will find that designs or the preference for certain kinds of jewelry styles will greatly vary from one region to the other. In India, that’s even more the case. India is an enormous country. You can almost think of it as a collection of multiple countries, and each of them will have its own history, cultural reference points, religious reference points, and jewelry styles. And so having a close pulse on those specific communities and being able to cater to those local tastes takes a very long time to develop. Titan has been at it now for just about 40-plus years, and so they’ve now developed that pulse.

In fact, an interesting tidbit is that on a recent visit with the company, they were telling us how they are trying to preserve a lot of the local artisan trades in jewelry that are slowly disappearing. Every region will have these very intricate styles that were developed in just that region. Some of them will use certain dyes to color their jewelry pieces. Others will use mother-of-pearl inlays to embellish the piece. Some will have specific brushes with which they carve certain pieces of gold. And on and on and on. It’s really a mind-boggling array of style varieties.

So Titan is now making it a point to go find these artisans in these local communities that are, to a certain extent, disappearing because, oftentimes, the next generation doesn’t really want to pick up the trade. They’ll go and work in an office in the city or take on some other profession. And so it’s making a point of preserving these trades by enrolling these artisans and ensuring that these local styles stay alive. So that’s an interesting thing that only competitors with the scale of Titan can do because, again, it takes a very long time to develop. But, again, to your point, jewelry is generally a more fragmented industry.

We think there’s still room for Titan to double its market share, and they’re now hitting an inflection point. In fact, not long ago, they had this target of maybe growing their market share by 30, 40, or 50 basis points a year. Since some of the developments in the markets, we’ve talked about the goods and services tax, we’ve talked about demonetization. Another important development, which came about recently, was hallmarking, whereby every piece of gold in India needs to be marked for its purity and therefore certified as pure gold, which again helps the formalization of the trade towards the likes of Titan and away from some of these more unorganized mom-and-pop stores that sometimes source their gold through either illegal ways or sometimes will melt the gold and then put other components in there to increase the weight in illegitimate ways. So they’re now talking about yearly market share gains of approximately 100 basis points per year. So there’s clearly an inflection point and acceleration in the market share, in the pace of market share gains that they can attain going forward.

But once they reach that 15 percent level, It is something to certainly watch out for because, if you look globally, there aren’t too many instances of local leaders attaining higher than 15-plus percent market share for some of the reasons that I mentioned.

Kevin Murphy (22:17)

That’s really interesting, and thanks for sharing your insight on that. It just reminds me that the term “a formalization of retail” in the emerging market space or developing market space is, in my opinion, an overused term, and what really matters is finding the specific examples of where it works, how it works, what the path forward is, and who will be the winners in that space. So that’s really interesting to take a look at that idea through the lens of a competitor like Titan.

And on that same thread, you mentioned the work you’ve done in India, visiting the stores. Can you talk to us a little bit about the on-the-ground research that you’ve done in the country? And then, as you mentioned, it’s a very large country. It’s more of a conglomeration of multiple country-like areas. I’m imagining it’s difficult to cover a space that big. How do you guys do it?

Massimo Marolo (23:09)

Yes, so it’s really one of the key strengths of doing research at Sands Capital, quite frankly. It’s a lot of this on-the-ground work to validate our thesis. So we visited many first-tier, second-tier, and third-tier cities and towns across India, speaking with multiple store owners and consumers. Sometimes, we’ll just drop in on a town, find a local jewelry bazaar or market, and just walk the street and randomly go into these stores and strike up a conversation with these store owners. Some of them will be more talkative, some of them will be less so, but, on average, it gives us crucial intelligence on what’s happening on the ground. Is Titan opening a store? When did they open a store? How has their own in-store traffic evolved since Titan opened a store nearby? How are the preferences of consumers evolving?

You know, one of the really interesting things we found out, especially after the pandemic, is that consumers are clearly spending more time online. Historically, when looking for inspiration, a consumer will visit their local jewelry store and ask that jeweler for advice on what pieces they should consider. But as you can imagine, these mom-and-pop stores are maybe 200 to 300 square feet. So there’s not a lot of inventory that they can offer in terms of breadth to help the customers get inspired. Increasingly, with consumers spending more time online, with Facebook or WhatsApp or whatever other online platforms, they step into that jewelry store with already a pretty well-formed idea of what they’re looking for.

And that helps Titan because its stores are, on average, 4,000 square feet. So there’s just a lot more to choose from. As I mentioned, they can hold anywhere from 150 to 500 kilograms of inventory versus five to 20 kilograms for the average independent retailer.

Now, other things that we’ve done, one of the more interesting studies was probably a video survey we deployed in 2020 during the pandemic because we couldn’t travel. And we interviewed local housewives to learn more about their gold-purchasing behavior and understand how the Tanishq brand resonated. Tanishq is now expanding in smaller, second- and third-tier towns, so it was becoming important for us to assess the prospects for their new stores.

Then, other things that we do on the ground are, obviously, we meet with management—as part of our research—with whom we’ve developed a relationship for over a decade. Their CEO, Venkat, loves to sing, by the way, so apparently even records his own tracks. So we always try to get him to share one with us. He hasn’t yet, but we’ll keep persisting.

Kevin Murphy (26:04)

So I know we’ve kind of moved beyond the competitive advantage, but you’ve also mentioned in the past that just their ability to stay ahead of emerging trends in the industry—sort of a fashion approach to jewelry. Can you go into a little bit more detail on that? How do you think about that with Titan?

Massimo Marolo (26:22)

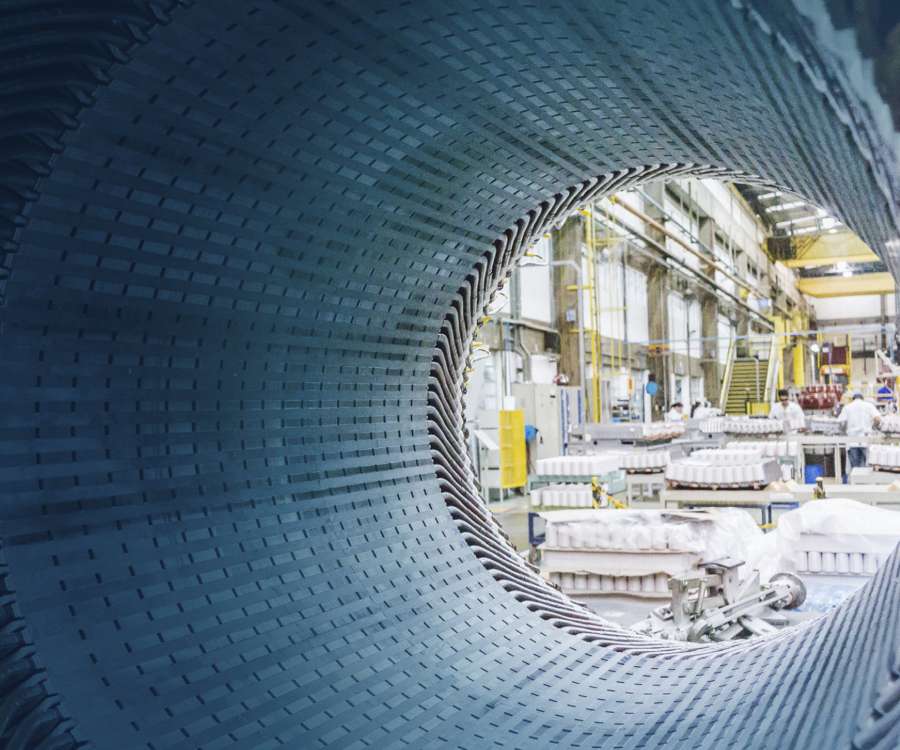

Sure. So what differentiates Titan from all other competitors, including other formal competitors, is that they are completely vertically integrated. And scale in manufacturing matters in a world where consumers expect brands to keep pace with their evolving sense of individuality.

To a certain extent, we believe a behavioral element seen in fast fashion that finds parallels in jewelry. So for example, Titan retains close to 3,000 employees in manufacturing alone, which exceeds the total number of employees of every other public competitor except PC Jeweller. Its R&D [research and development] department, which it calls the Center for Innovation and Technology Excellence, is recognized by the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research for its innovative capabilities, including the utilization of technologies such as CNC [computer numerical control] machining and later in additive manufacturing. So they’ve always invested a lot in manufacturing. Historically, that was very important; it always was.

But I think it’s now becoming even more important because you’re seeing the consumer journey starting more often online. And, as I mentioned before, increasingly, the consumer walks into a store and already has a pretty good idea of what they’re looking for. This is new. This is a relatively recent phenomenon, and, to a certain extent, we think it’s still not well understood, but it’s definitely happening.

Our own conversations with other mom-and-pop jewelers confirmed this, whereby they say there used to be a time when a consumer would walk in with no idea of what they wanted to buy, and now they walk in sometimes with a picture that they’ve taken somewhere online asking, hey, I want something like this. And so this really favors the vertical integration that Titan has built over many decades because it gives them the flexibility to respond to these demands and produce these pieces much faster than anybody else can.

I’ll give you some other examples. When Titan, as we mentioned earlier, gets 40 percent of its gold through the exchange program, that in itself implies the ability of having a very fast turnaround and being able to accommodate the kinds of styles that the consumer wishes for. If a consumer brings their piece to another smaller jeweler and asks that piece to be recycled and restyled in a certain way, that jeweler is going to have to send it to some other entity to do the actual work. That all adds time. Increasingly, as you know, consumers want things as fast as possible. So the ability of having a completely vertically integrated operation gives Titan a speed advantage when you have more of their customers bringing their gold to be recycled into new pieces.

So these are just some of the examples. We can go into more, but those are some of the observations that we’ve seen in terms of the importance of them really having built manufacturing over the years.

Kevin Murphy (29:46)

Yes, on that same kind of line of competitive advantage, you mentioned procurement. Talk a little bit about gold-on-lease. What exactly is that, and how does that work? And how is that an advantage for Titan?

Massimo Marolo (29:57)

Yes. So basically, gold-on-lease is a scheme or program whereby you can either purchase gold and take out an inventory loan or deposit an amount of gold with your jeweler, who in turn will replace that gold with a piece to your liking. Historically, what a lot of people did to buy gold was take out an inventory loan. But that carried a very high interest, often 10 to 12 percent interest. And gold-on-lease schemes are not available to the smaller jewelers because they do not meet the bank credit or transparency requirements. Whereas, larger entities such as Titan can procure the gold at reasonable rates and therefore have an advantage in the financing that they’re able to then offer to the end user. And again, as the economy is slowly formalizing, these financial schemes are becoming more important because they’re ultimately translating into better terms to the customers that some of these unorganized jewelers aren’t able to offer.

Kevin Murphy (31:12)

Excellent. Yes, so another question that popped up in my mind, as you mentioned, is vertical integration, which kind of leads maybe to the next topic of stewardship.

Massimo Marolo (31:24)

Sure. So the supply chain of gold is a tricky one because it involves mining, as you mentioned, which is done mostly outside of India, throughout the world. And that presents a lot of opaqueness in the supply chain. Mining is also responsible for a fair share of greenhouse gases, and it is also prone to unfair labor practices. There are instances of modern-day slavery, which unfortunately afflict the mining profession.

We actually, just two weeks ago, engaged with the company on such topics. They reached out to us and took the very progressive step to approach us as one of their top shareholders, knowing that we do a lot of work on sustainability. And so they approached us to seek our thoughts on the topic.

There are things that could be done. It is nowhere near perfect of a supply chain. But there are steps that can be taken to improve tracking of their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, for example, and eventually even move towards Scope 3, which, in the case of mining again, might be unrealistic simply because it is done outside of the country, and it is often done in countries that themselves don’t necessarily have best practices. So as is the case with diamonds, there is a process via which this gold is increasingly being certified. Hallmarking, which I mentioned before, adds an element of legitimacy to this. But also, going back to the Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, it would certainly allow them to better track the emissions at the upstream point where gold is extracted.

It is a journey. It is not something that’s going to change overnight. I think the fact that they approach shareholders like us to seek our thoughts is an important first step. And it’ll be an evolution. The company has started to issue sustainability reports where they are starting to track and even commit themselves to certain targets. But it will take time.

And it is a big industry. There is a lack of transparency along certain segments of it. But again, it’s small steps that, over time, can end up making big progress.

Kevin Murphy (33:48)

Yes, and I guess, if done right, it could be an advantage for a company like Titan, whereas the smaller players in the space don’t have the, I guess, flexibility to do that or maybe the moral compass to know that that’s something they should do. And if purchasers, if the customers are increasingly demanding to know the provenance of the gold, that could certainly be something that puts Titan ahead of the rest.

And it reminds me that you have in your investment case, an interesting kind of, I guess, back-of-the-napkin equation that I think sums up this entire conversation pretty nicely. Brand trust plus service plus transparency equals volume growth plus industry consolidation plus potential for higher margins. I think that’s an interesting framework to look at how this business side on the left side of the equation is doing the right things in each of those categories and how that results in the outcome on the right side of that equation. So it’s kind of an interesting way of thinking about it.

Massimo Marolo (34:47)

That’s exactly right. We’ve developed a high relationship of trust with management over the years. They are adamant, for example, about hiring the right employees. All new hires come from a store’s local area and must have intimate knowledge of prevailing customs and style preferences.

All new recruits attend a month-long training program and undertake periodic refresher courses. In fact, if you look at the attrition rate, employee turnover at Titan is about 10 percent, which is half that of the industry. And if you look at how much it spends on labor, that’s about 5.5 percent of sales, while public competitors are at about half that. So it’s really a company that is also cultivating its own employee base with a lot of care, which ultimately translates into better operations, better transparency, and higher trust that the customer has in them as well.

Kevin Murphy (35:51)

Yes, excellent. It just is a way to protect that substantial moat around their business. Well, we’ve covered a lot of ground here, and I’ve taken you in multiple directions. What have we not talked about? What questions didn’t I ask?

Massimo Marolo (36:04)

We’ve covered a lot. Perhaps the one thing we’re most excited about is the next stage of Titan’s growth, which is one of brand elevation. Here, you have an already dominant and trusted brand that has served the Indian consumer for over four decades. And India possesses arguably one of the most vibrantly expanding middle classes. Just imagine that the number of people who enter Titan’s affordability threshold for the first time is expanding by 7 percent to 8 percent per year. These are just people who are graduating in terms of affordability threshold and coming into the segment of society where they can afford buying branded jewelry. And then, on top of that, for those who’ve already crossed that affordability threshold, they are seeing their own disposable income grow by 6 percent to 7 percent.

So there’s a lot of layers there that are building on top of each other, that are essentially creating a next stage of growth for Titan, where gold, historically seen as a necessary adornment for weddings and even a source of investment, is transitioning to something that is more reflective of a person’s own sense of style and individuality. So, we’re excited about this next stage of growth, given the favorable macroeconomic backdrop that India is presenting, and that’s why we think Titan can continue on its journey for many years to come.

Kevin Murphy (37:40)

Excellent. Well, Massimo, thanks so much for spending time with us today. It’s a fascinating subject in and of itself, but you cover a lot of very interesting companies, from specialty chemicals to soy sauce, and so on. So it’d be great to have you back on the podcast at some future date.

Massimo Marolo

It’ll be a pleasure, Kevin. Thank you for having me.

Disclosures:

The views expressed are the opinion of Sands Capital and are not intended as a forecast, a guarantee of future results, investment recommendations, or an offer to buy or sell any securities. The views expressed are current as the episode date and are subject to change. This material may contain forward-looking statements, which are subject to uncertainties outside of Sands Capital’s control. The securities identified do not represent all of the securities purchased or recommended for advisory clients. There is no assurance that any securities discussed will remain in the portfolio. You should not assume that any investment is or will be profitable. A company’s fundamentals or earnings growth is no guarantee that its share price will increase. For more information, including a full list of portfolio holdings, please visit our website at www.sandscapital.com.

As of May 30th, 2024, Meta was held in at least one Sands Capital strategy. No other companies mentioned were held in any Sands Capital strategies at the time of recording and were mentioned for illustrative purposes only.